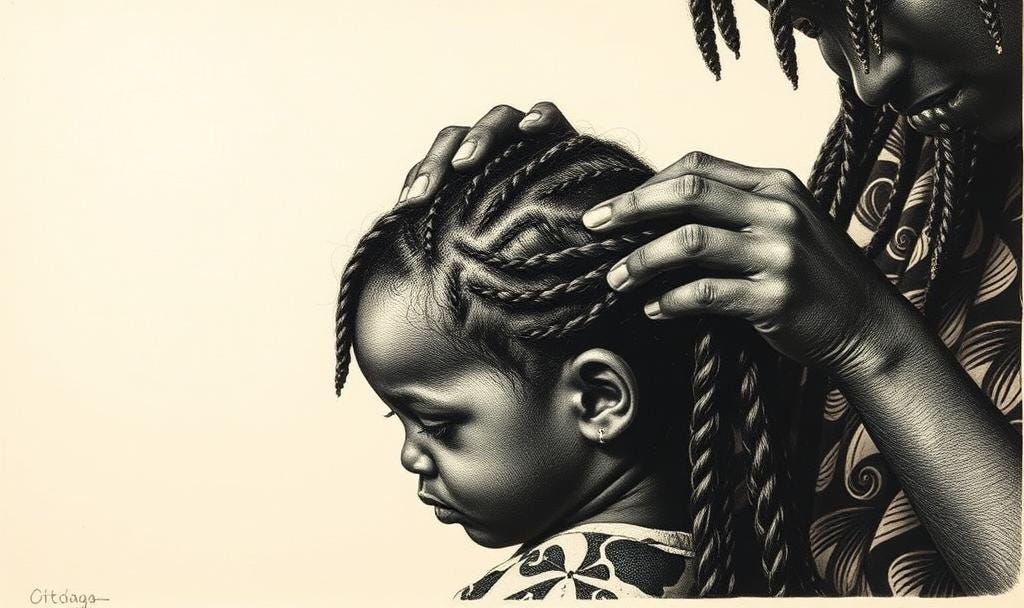

Her hands made art with your hair.

Sometimes, she would make zigzagged cornrows, and on other days, she would weave a simple patewo clasped so tight it resembled a prayer.

First, she carefully divided your dense afro into sections and traced Sulphur 8 pomade in the lines she made with her rat-tail comb. Then she would give your scalp a gentle rub and tell you stories of her home as she sectioned your hair into plaits.

You played with her daughters afterwards—building sandcastles and chasing chickens in the courtyard. Sometimes you brought akara to them, thick bean cakes from the Saturday breakfast table.

As you grew older, you heard the whispers of the women whose stalls lined the street leading to her house.

You heard snippets of words you were too young to understand, but you learned quickly.

You knew they avoided her at social gatherings. The only reason they spoke to her at all was because she weaved the best braided crowns—her hairstyles were the envy of women in the neighbouring towns.

You heard loose lips call her unspeakable things, and caught them tugging their children's ears, warning them not to play with Mama Lape’s children—even the women who shared the large compound in which she lived.

Their husbands approached her in secret, and when she warded off their advances, they fanned the flames of rumour and gossip.

Your mother was the only one who let her children play with the hairdresser’s daughters.

She always paid more than Mama Lape charged for her services and handed her packages laden with garri and dried fish.

Some days, you came home from school to find the two women seated in the foyer, discussing everything from the military regime to the rising prices of basic commodities.

The townswomen traded whispers among themselves, but no one dared question your mother, for they regarded her with fear and curiosity.

Time passed, and your family moved away to the state capital.

You did not think about Mama Lape, not even once, until you sat on a low stool beside her, twenty years later, her kohl-rimmed eyes pooling with tears.

She had come to pay her last respects to your mother.

She no longer braided hair because she suffered from arthritis. She almost looked the same, only time had washed her out—like she had begun to fade into nothingness because she could no longer make beautiful patterns with her hands.

"Your mother was kind to me. She was a good woman," she said, wiping her eyes with the edge of her wrappa.

Mother, whose laughter tickled the ears, easily filled a room with her kind and affecting presence.

You shifted in your seat.

She was.

Mother was gone, but you preferred not refer to her in the past tense. You would never be ready for that finality.

“She was the only friend I had in this town,” Mama Lape started. “My father was a gambler and owed several debts, and I was given away to a moneylender to settle them. This man—my husband—had a sour temper. I could never please him. If the soup was too cold, he would beat me, and if it burned his tongue—tut!” She shook her head.

“The man beat three babies out of me, and one day, I took his money, tied Lape on my back, and ran. I was pregnant again.”

She rocked back and forth in her chair.

You looked away as the weight of her confession settled into a knot in your belly.

“Your mother knew this, and showed me great compassion. I made her keep my secret because I did not want that man to find me.”

Your mother was slender and graceful, floating in many layers of fabric, offering firm kindnesses to all who knew her.

She was gone, but the stories remained.

You savoured them, writing journal entries of women who told many tales of her fierce goodness.

Your only wish was to be half the woman she dared to be.

At last, Mama Lape spoke of her children—Eniola was studying to become a doctor, and Lape had just completed the National Youth Service in Ibadan.

“I used to plait your hair, remember? Is this how you city girls wear your hair now?”

You laughed.

Over the years, your hair had bloomed and withered without her, suffered the sting of hot combs, relaxers, and steamy hooded dryers.

You had worn it long and short, in boyish cuts and in elegant twists that fell to the base of your neck.

Now, you wore your hair in a closely cropped Jheri curl, painted a spicy red.

“Yes, I remember.” You smiled, and pictured your mother—elegant in a yellow boubou, a bag of combs and ointments in one hand, your hand clasped in the other—floating down the winding road to the hairdresser’s house, skirt billowing in the wind.

Then, you became awash with emotion and wished the old woman would leave so that you could cry, and cry in peace.

It ended too soon!! I wanted to keep reading. I wanted to keep reading the stories of Mama Lape. It was such a beautiful read!

Your words leave such heavy emotions. I didn’t realize until I exhaled loudly, that I had been holding my breath, silently trying to decipher whose stories formed the basis of this midnight catharsis. Brilliantly written, sis!